16 A Conversation with Kevin Mack

A Conversation with Kevin Mackby Axel of Brainstorm, Menace of Spaceballs, and Okkie of Limp Ninja

Download the pdf here

Back in 2007, ZINE organized a presence of the demoscene at Siggraph, together with the organizers of the Computer Animation Festival headed by Paul Debevec. At some point we were asked, if some members of the demoscene would be willing to join a panel discussion after a presentation by Kevin Mack. Mack would be interested in talking to some demosceners about real-time computer graphics. But who was Kevin Mack? Shortly after conducting a Google search, our jaws dropped.

"I was really just an artist to begin with..."

Mack is an Academy Award winning visual effects supervisor, who worked at Digital Domain and Sony ImageWorks and has worked on movies such as The Abyss, Vanilla Sky, The Grinch, Fight Club, 5th Element, A Beautiful Mind, Big Fish, Apollo 13, Ghost Rider, Speed Racer, Percy Jackson, and many more. Sceners like Kusma and iq went to Siggraph to join the discussion, and generally a good time was had.

Quite a few months later, ZINE had an opportunity to talk to Kevin Mack. The conversation lasted about three times as long as scheduled.

Kevin Scott Mack, born in 1960, is the son of Brice Mack who worked at Disney as a background artist on famous movies such as Fantasia (1940), Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951), Peter Pan (1953) and Walt Disney's Wonderful World of Color (1956). Kevin followed in his father's footsteps. "I was really just an artist to begin with, and I still am," explains Kevin. "I keep making art, and I started out as a painter doing abstracts and whatnot. Once I started college I had been an artist all my life, so I wound up doing visual effects for a living. I got very interested in computers for making art - kind of before it really was a viable option for visual effects or anything. It really was quite new when I got into it. So when the computer graphics took off for the visual effects industry, I was kind of at the right place at the right time. I had been doing traditional visual effects work,- matte paintings and miniatures and whatnot - and I had a bit of experience there, but I'd also been doing computer graphics just for art. I've been making abstract animations, procedural models, l-systems, and all kinds of crazy stuff for making images with the computer. It is really my son who is into the demoscene, and he turned me on to it."

An Academy Award winner is interested in the demoscene? That was unheard of up to that point. "My son is a computer guy, and far smarter than I am," says the proud father. "He just reads everything about computers and the whole scene, and so he knew I was into abstract stuff and he's into it as well. He started showing me demos, and when he first showed it to me, I was just blown away. I was like, 'What is this? How do they do that?' And so, little by little, he educated me. I still have a lot to learn. I learned a bit at Siggraph from you guys, and I'm pretty into it. It's pretty exciting." He can't remember exactly what the first demo was that he saw, as his son showed him a bunch in one day. But he remembers that Farbrausch was in there. "When he first started showing them to me, I was really into them, but I didn't really know what the demoscene was, and I couldn't figure out 'Why are these people making these things? These are cool, but I know from experience that there isn't much mainstream awareness of making abstract art. He kept referring to it as if it's this thing - like 'The Demoscene' - like it's some kind of official 'thing' that people do. I was just really surprised to find out that it existed. It's like a secret society."

"It's like a secret society"

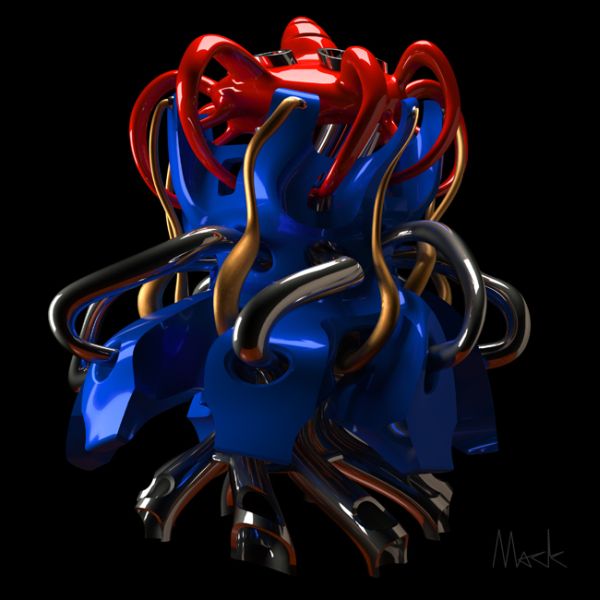

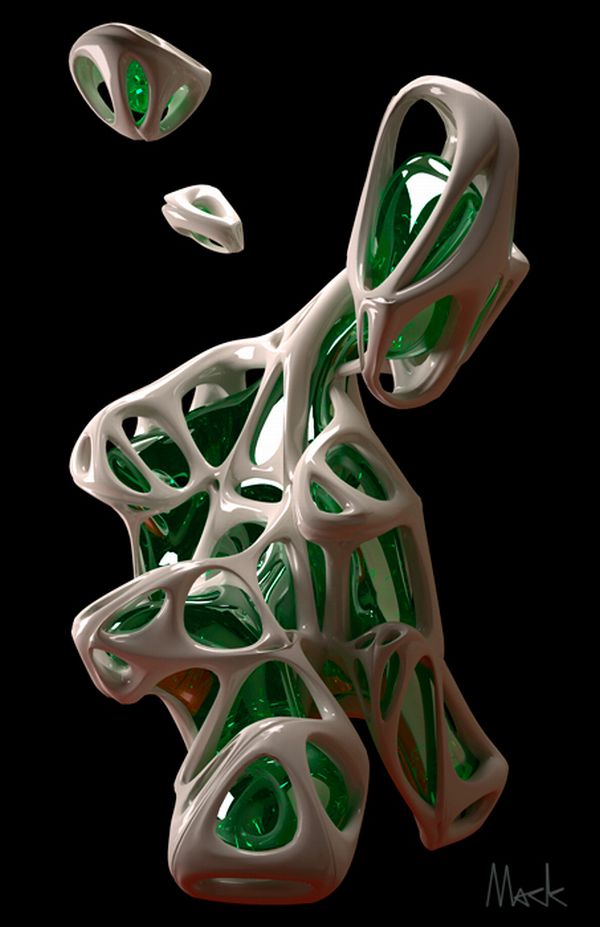

When he's not working on multimillion-dollar blockbuster movies, Kevin Mack is working on his own personal abstract art. "Most of what I do happens at the shader level," as he explains the process of generating his art. "I do a lot of different things, so it's kind of hard to just sum it up. I do a lot of procedural stuff, I do a lot of rule-based stuff. One of the main things that my work has in common, is that they often use a lot of turbulence, random functions, and/or noise functions. I combine a lot of those things in strange ways. I will do odd things like a divide which you wind up dividing by zero, which generally people frown on. But I have found that you can get very interesting results by dividing by zero, as long as you don't only divide by zero. You get some interesting singularities that result in some bizarre discontinuities in images."

This is the first time ZINE hears somebody actually talking about dividing by zero in a positive way.

A 3D print sculpture made of one of Kevin's artworks.

"Yeah, I came from it all," he laughs. "I was just an artist, so it was more of a visual thing for me." Because he started into computers pretty early, there wasn't anywhere you could go to learn it. He was committed to figuring it out, so he learned to program a little bit and it only took a few years for him to realize that he would never be that good at programming. "But I think it's helped me a lot to know about programming, and what can be done and so on," he explains. "And the other thing is, tools emerge that allow me to do basically programming, but it's nodebased, and I don't have to remember syntax and search through lines of code to find where I mistyped a colon. I can just see a graphical representation of the code. I still write pretty elaborate expressions at the end of the day. It's weird too, since it's kind of a hybrid. I don't work exclusively with mathemathical functions, a big part of what I do is done by hand. So, a lot of time what I am feeding these functions are paintings that I've made, generally in the computer. But they're images to begin with, so it gives me a little bit of... well, I tend to avoid the purely mathemical. I find that adding a little element of human generated component helps to make it more interesting, or disguise how it was done." So what comes first? The painting or the mathematics? "I like to work all the elements simultaneously," he elaborates. "Not literally, but I'll be working on images, I'll be painting and then I'll work on the functions... And I generally test the functions with some standard images that I use, to visualize the functions. Those are very very simple, since they help me to see what the function is doing and to get my head around how to adjust the functions. It's really an awful lot of trial and error and artificial selection. I make a lot of stuff, and throw most of it out. I'm really into the thing of using these random functions, and differnt things that are at least partly contrived in that I have some notion of what they're gonna do. I'm mostly interested in the things that are mostly just a fluke, that I stumble on to. Generate a bunch of them, and there's always one of them in there, or two, where you go 'my god, how did that happen?'"

Sounds a lot like democoding.

For that reason, Kevin Mack really looked forward to meeting demosceners at his panel discussion at Siggraph. "I thought it went really really well," remembers Mack. "The guys on the panel were fantastic. Everybody just seemed really interested, we had a big crowd, and people were really into it. And the guys showed some demos, and we talked about the demoscene a little bit. I kind of wished it had been longer, because it seemed like we were just getting started, and the crowd just seemed to want more, and to know where." Hundreds of people attended.

"My god, how did that happen?"

A great synchronization between visuals and music is something that Mack is equally trying to achieve like the demoscene does. "I tried that particularly in the animation I had made for Siggraph. I think it depends on what you're trying to achieve in the end. I'm working on a piece right now that is a little different, in that it's a very slowly evolving piece. it's more like an ambient track would be ... it's kind of a relaxation art piece that you could have on your flatpanel while you're having a dinner party or something. So, that one's really designed to go with chilled music, rather than having it be something you focus on completely." Sounds like Chimera, a really slow moving demo that was loved by people, and equally hated by others. "It's really another part of the fine art thing, I'm trying to get into some shows and galleries that show video art. I guess they sell limited edition video art. It's hard for me to imagine who buys that, but...you know, when you could download all these demos." He laughs. "I don't know, it's a strange world, the art world."

There's news spreading that there are galleries thinking about running demos on screens too. "Yeah, I think you guys could clean up, I really do, because when that thing you're selling is actually a program that's regenerative rather than a recorded video of something you made, they really like that. Programming as art."

"With 'they' you mean galleries," ZINE asked. "Yes, there's a whole kind of scene for that," Mack replied. One would think that galleries are very traditional, so it's a bit of a surprise that they are open to new kinds of art. "It's a very small subset of the art world," elaborates Mack. "There are some pretty high-end galleries that are starting to sell that kind of thing, and specialize in that kind of work. I sell these prints on canvas that are large, and pretty traditional - or trying to be somewhat traditional in their format. They could hang in any gallery or anyone's living room, but people keep saying that 'you do animations, you ought to get on that because animation art and video art is all the rage in the art world right now.' Guys, we should open a demoscene gallery." ZINE points out to him that he is the one with the contacts. Mack laughs, and adds: "Oh well, I wouldn't say that at all. That's a tough one. I kind of thought I could use my notoriety in the visual effects world, and my Oscar and all that, to serve as some borrowed interest to get me some interest in the fine art world. I found that if anything, it works against you, because as an artist you are supposed to be starving or dead or something." But if the attitude is that artists must be really poor, then Mack probably is the absolute opposite of that. "Well, yeah, I think success in one area, if it's commercial, will make them figure you are not as committed to the fine art. I don't know, I'm baffled by it, personally. I certainly understand the difference. I love doing visual effects, but that's a way different process in that it's so collaborative and everything. What I love about making my fine art, and why I've kept doing it is because it provides me with an outlet that is all mine. Nobody's telling me what to do, I'm not aiming to please anybody."

An artwork Kevin called the Counsciousness Engine

Mack very much sounds like a demoscener throughout the whole conversation. The demoscene is pretty much about the same things that Mack describes. About doing what you want to do, and making anything you want to make. No rules, no boundaries, no nothing. "To me that's what makes it fine art and not commercial art," says Mack with a nod. "I definitely see the demoscene as fine art, and a lot of the things I've seen just blow my mind. I think it blows away the stuff I've witnessed in fancy galleries."

For every demoscener out there, this should be nice to hear. There's been a major discussion in the demoscene for years about whether demos are actually art or not. It started out as just coding effects and showing them on computers, back when there wasn't really much going on with computers. But we see it more and more now, especially with the PC, where the technical limits are really not that important anymore, a lot of people are starting to focus on design, more messages, and conveying emotions and ideas.

"The one thing that I would say is that maybe a cultural difference, that's kind of hard to figure, is the whole collaboration thing. I guess there are some 'one man bands' in the demoscene, but from what I understand most tend to be whole teams of people. And in the fine art world, it's a one man deal, a solo effort. Although that's really not true, because a lot of the most successful artists have big staffs of people working for them. It's just that at the end of the day it's one person's name that goes on it. The other people get paid a salary or something." And in the demoscene it's a group effort. "It's interesting, cause that's true in the film business as well. I don't think a lot of people realize how collaborative the film industry is. It's set up in such a way that the directors and the director's guild is so powerful that the way credits go and the way the industry works, they really just sell the idea that it's one guy's vision."

To what extent is there still artistic freedom when making something for a movie, ZINE wanted to know. "It's different on every project, and with every director. Every filmmaking team has a kind of different way of working. There's some cases where you're kind of just executing an idea for somebody else. But generally it's not all figured out, so there's a lot of decisions to make. I've been really lucky, because I've gotten to work with folks who have been really collaborative. In many cases the director is responsible for so many elements of a movie that they can't possibly do them, or even make all the decisions. So, if they find someone who they can trust and that they relate to creatively, more often than not, they are pretty thrilled to have somebody just take it over. I've been lucky in that way, and I've had directors just kinda go 'whatever you think is best, just do that.' And then there's other directors where it's really cool because you get to collaborate with them and they have really cool ideas. They're just fun to work with. They're brilliant people, and you want to learn from them."

Many demosceners think of Tim Burton when they think of good directors who could make great demos. "Yeah, Tim was happy to just have stuff solved. He knew that you were going to do the general idea that he was looking for. He's a great guy. He's a real artist, not just a filmmaker. He's an artist-turned-filmmaker. At one point I asked him about it, 'How do you get to make films like this?' And he said: 'If I had come along now and asked to make these films, they would never let me make them. Cause I'm just an artist, I'm not a traditional filmmaker. I've just been really really lucky, and got away with some things early on, so now I get to get away with stuff that they would never let anyone else do.'"

Over the last two years, the discussion has repeatedly come up how many commercial doors the demoscene should open. Should large companies be welcomed to sponsor events? Or not? Same goes for whether demoscene groups should do productions for corporations with a commercial background. "I think where it gets sketchy is where you draw the line," thinks Mack. Because I think it is important for there to be a line. I think it's perfectly fine to do work for hire, and to work for clients that have one agenda or another. You are working in service for those people, and doing what you can for them, offering your help, but when you're doing fine art... for me, that's been a big part of my success. I'm really good at my job, of helping people with their visual effects, because I'm not that invested in it from a personal ego standpoint. I have my own art, and so the work I'm doing doesn't have to be 'my way', it just has to be good. I just try to stay kind of professional about it. There are hundreds of right answers here, it doesn't have to be just the one I prefer. It can be any one of these right answers, and my job is to make sure it is one of these right answers, and that the work is good. I contribute creatively, but they can take or leave my ideas, and no hard feelings. Because it's not my art, it's their thing. I'm just helping out. But I'm able to do that because I make fine art, and I defend it rather rigidly in that whenever it starts to turn into a commercial thing, people want to buy them, or sell them online and stuff. And I get galleries and other people that will say, 'Oh, if you just change your palette to this', or 'if you just did this thing', you could sell it like hot cakes or something. It's just that, if I did what they are asking then it just wouldn't be my art anymore. It wouldn't satisfy the need I have, which is to express the vision I have pretty explicitly. I think that as long as those things stay straight, it's okay."

Okkie of Limp Ninja comments: "I think there should be a line. Because there have been demos made before that ended up being sold as screensavers, or as small advertisements, and it's always been kind of frowned upon in the scene itself. 'Why are you selling your stuff, and making money off of it? You should enter it in a competition,' people said, and it's a bit of a hard line. You see a change, and looking at that change myself and thinking about it - I've been a demoscener for about 15 years - and when I started it was like all for fun and coolness. All of a sudden now you see that there is much more interest in it. So where does it go indeed, where does it lead to? Do you think there are any downsides to getting more exposure? Because there are always worries about legal aspects for example. Especially in the beginning of the demoscene there was a lot of music sampling and graphics stealing, copying and stuff going on. You see it now getting harder as well, like at parties copyrighted material is no longer being allowed to be used."

"I'd be careful what you sign, in terms of companies wanting to show your stuff," advises Mack. "But I don't think there's an issue with selling your stuff as screensavers, or stuff like that. If you can sell something, that's good for you. Where it gets compromised is where it becomes confusing trying to figure out 'is this my art'? Suddenly Nvidia comes along and goes 'We'd like you to change all the colors and these crazy patterns to say Nvidia,' and then you're like 'Hmmm yeah, I don't know...'"

Being the anarchistic community the demoscene is, it seems unlikely that corporate logos would happily be placed in demos to get an extra dollar. "Yeah, I would think so," agrees Mack. "And I would think too, you guys ought to stick together and keep and eye out for each other, because your stuff is the kind of stuff that could get stolen and show up in some tv commercial or web ad. As long as you guys are watching out for each other and go, 'Hey, I know that! That's Fairlight's work right there!' and let them know, because that's against the law. Some work of yours ended up on a Nelly Furtado album, right?"

"Yeah, that happened few years ago," we confirm. "There was a song on a Nelly Furtado album, that was basically a chiptune made by Finnish musician Tempest. The demoscene grouped together, and it caused quite a ruckus on the internet. People screaming about the theft, and finally it was settled. "Right, of course. That's always the deal," replies Mack. "It's interesting though, now that I think about it. Most folks at big companies, they'd be stupid to mess with you guys. You guys can write CODE. You could take down their servers, you could ruin their lives."

The free availability of demos on the internet also caused concerns that companies could steal these contents without the demoscene's knowledge. "I don't think it will be too big an issue," thinks Mack. "I think you guys will get more well known. I'm excited about it because I think there is room for other mediums of art rather than the traditional narrative, the storyline thing. With characters, their relationships, and their problems. With games being so big and all, I think even that has become sort of narrow in its scope. It's always the same sort of thing for the most part. The game, with its goals and its objects, and shooting things, or chasing things, or solving puzzles. I think there is a place, especially as the fidelity of real time improves, for imagery etc. that is strictly experimental. Where you're not trying to get a story out of it, or necessarily even a comment on society or anything. It's more like, 'This is just stunning to look at and listen to.'"

That leads us to another passion of Kevin Mack: the brain. Mack is a honorary neuroscientist from the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. He gave some lectures there on perception, creativity and consciousness. "Neuroscience is kind of like a hobby for me. And it's neuroscience, not neurology, I don't do surgeries." Laughter. "I'm not a doctor in that way," he continues. "But I've read about it for years, and I like all the artificial life stuff and neural networks and all of those things. Really, what I do in visual effects as an art, I'm very interested in perception and esthetics, and how people perceive images and the order in which they process this information. It helps to be able to create illusions and to trick the eye, and to be able to guide experiences for someone, when you know how their brain works in that regard." Surely that is an area where constant research is of the essence. "I try to keep up with it," he admits. "I'm doing research into some stuff now. I brought up a little on the panel, there's this brainwave intrainment that is kind of an interesting topic. You know you've got your EEG, your brainwaves, and they occur at a certain frequency or frequencies. They generally have lots of frequencies, but there's often a dominant frequency. And depending on your state of mind, that frequency varies. They have found that you can actually get a brain to sync to a specific frequency using pulsed tones and pulsed light (strobing light glasses). The brain will sync to that frequency, and then of course, the person will enter the associated state of mind. So it's possible to induce a particular state of mind, like meditation, or a hypnotic state, a highly suggestible state, a state of heightened awareness, alertness, or an altered state. There are people selling it for extremely legitimate causes. It's very well documented that it works. Of course there's lots of people selling it for everything, from legitimate uses, to pretty exotic things, like out of body experiences and .. channeling gophers and whatnot." Sounds like something the demoscene would like to play with. "Yes, that's what occured to me," he adds with a grin. "Because I've seen a couple of demos that were clearly psychoactive, at least in places. It's a big part of why electronic music is effective. It's syncing your brainwaves to a certain state."

This rings a bell in Okkie's mind. "I actually got this song a little while ago, that's indeed like this little audio drug that they have. It's more like a soundscape. Listening to it, you feel yourself getting into a different state. It really works! I just put it on, sitting behind my computer being a real sceptic about it, but I felt different listening to it."

"Yeah, that probably is brainwave entrainment," agrees Mack. "That's one of the big things they do. They have a lot of different techniques for embedding those pulsed tones into music. Even to the extent that you can't even hear them or notice them, and yet they're still there and will do little amplitude modulation, or a slight sync thing between the two speakers. They have all kinds of different techniques that make it less overt, and it's very effective. They've shown again and again how it's very effective and I know from my own experiences that it seems to work pretty well on me. So I've gotten into some software where I'm fooling with patterns and basically creating my own programs of different frequencies and experiment with different frequencies, and different sequences of frequencies. I make different combinations of them, to see what kind of effects they can cause. That, along with the psychology of color, motion, and just pure esthetics, is allowing art to evolve in interesting and powerful directions."

"Your stuff has inspired me!"

Diving a bit more into Mack's movie works, one film stands out that pretty much everyone likes - Fight Club. "Well, I did the opening title sequence which is pulling back through the brain - it starts in the synapse as the synaptic vescle breaks and the fluid is released and there are hormones and then transmitters are released into the synapse and we pull back through neurons, through the dingriddic forest and all that and right on through the various cavities around the brain. Then you come right through the skull and you go down through the skin and the nose of the guy to reveal the barrel of the gun, and it's in his mouth," explains Mack. "So it's kind of like you're following his thought. It was kind of a seminal thing when we did it, and since then I think CSI has pretty much built their whole style based on that shot. I have seen numerous other things as well. Medical visualisations that really look like it. Discovery Channel types of things. At the time, I have associations with people in the neuroscience community, some of the top neuroscientists in the world, and they said it was the most realistic and accurate visualisation of the brain that had ever been done at that time. It was pretty cool. Anyway, I'm very proud of that piece. I also did a thing in there, where there's a scene where the character falsely dreams that the plane he is on is coming apart. That a small plane has hit his plane. You see the whole side of the plane peel away and everybody and everything is getting sucked out. I did that shot, or shots, and I'm actually in that shot. As the camera pans around it reveals a guy that's hanging on for dear life to his seat, and it's shaking violently and he's being pummeled by all the little bits of luggage and little single serving liquor bottles and creamers and silverware. That was me." ZINE asks if it understood that correctly, that he got beaten badly by all the objects flying at him. "Yeah. And I'm there, it's full screen, you can see me. It's not a quick cut or anything. I'm in the movie. It's pretty fun, I'm awfully excited that I actually got to be in that movie, because I think it's one of the coolest movies ever. It certainly was a great one to work on. I'm a big fan of David Fincher, and I was talking about working with different directors earlier, and he's a blast to work with. He's just really fun."

Is it possible to feel that a movie is something special when you're actually working on it, before all the marketing machinery kicks in? "You know, it really depends," says Mack. "It's hard to tell sometimes. Sometimes you think a movie is good, and then it doesn't turn out to be that good. Or it's good, but it doesn't do well. Other times, you think a movie is gonna be terrible, and then it ends up doing really well, so... It's pretty hard to tell. Once in a while you can tell right off with some movies, as certainly was the case with Fight Club. I read the script and it CHANGED me, you know? It's like getting hit in the stomach or something. Just so powerful, it makes you wanna re-evaluate your whole life. I think the power of that kind of story and that kind of movie is why it's such a cult classic. And when it came out, it didn't do that well. There is still a lot of people that put that as one of their top movies of all time, and I'm one of them."

When it comes to picking what he's most proud of, the answer comes fast. "My kids," he says. "My kids are pretty cool. They're grown up now, but they've turned out to be really cool guys and very, very talented. As an artist, I'm into the artificial life and the procedural, rule-based systems, and all kinds of generative art and everything. I realized one day when I was listening to my son playing the most beautiful piece on the piano and he was just improvising it, that I had achieved my goal in them. I always wanted to make something that made things. It has never been enough for me to be an artist. I wanted to make art that makes art, and will continue to make art after I cannot make it any more. And I guess I feel that's how it is with my kids."

Kevin Mack has two sons. One is 28 and the other one is 24. They're both artists and musicians. Ray Mack is a DJ and musician. "You guys should talk to him, because he does music that is very, very well suited for demos," adds Mack. "It's original, and also it's pretty cool." The second son is a computer genius and an incredible artist, and he's working for Activision right now. He's the one who turned me on to the demoscene." But he's not a scener himself. "He hasn't done anything for the scene yet", explains Mack. "He kinda got into it like I did, and then he learned the software with procedural tools and whatnot. He's done a bit of coding, but I think he's reluctant to go there as well. I think he's still figuring out what he's going to do. He's got an awful lot of cool choices, since he has both the brilliance on the technical side, and... you know, he builds machines and specs them out. So he's really brilliant in that way. But he's also a really great artist. He takes amazing pictures, and he can draw, and model, and paint, and all that." ZINE suggests to Kevin Mack that he should make his son attend a European demoparty. "I think he'd be thrilled," says Mack. "He idolizes you guys. He thinks you're awesome."

Kevin Mack with his son

Good to know, so at least someone does.

"You guys - your stuff has inspired me," he declares. "I see some of these things, and I can't touch them. I can't do it. I'm kinda getting into the real time thing now. I've avoided it for a long time, because I just felt like I kept looking at the games that my boys were playing, and I just go 'yeah, that's pretty good, but it isn't quite there yet.' You know, compared to what I can do in, like, 59 hours of frame renders. But now I'm starting to see stuff, like, real-time ambient occlusion. Say, what? I'm seeing stuff, that I go, 'OK. I think I'm ready.' I'm ready to start jumping in and figure out how I can do this stuff and get involved. I'm still struggling with trying to figure out how it all works, and the whole collaborative thing throws me off a little bit, it becomes a little confusing in like 'Is this my art, or is this a job, or is this a club?' You know, where do I fit here. How can I help, and how much can I help in it all."

The fact that demos can take up anything between one to 24 months to create is not new to Mack. "I can imagine, because I make these things too, and my stuff isn't real-time. So I imagine it's in some ways easier to produce. And yet at the same time, I'm drawn to the real-time thing but I also kind of want to go 'where are the tools that will allow me to do my own stuff by myself.' I don't know why that is, there's just kind of a thing there. It's not like I'm not used to collaborating. I collaborate with about 100 artists or more on just about every movie I do, and I really enjoy it. When it comes to my art, I kinda want to keep it to myself somehow. I'm torn. I don't have it figured out just yet."

Kevin Mack even looked at some of the demotools, but ZINE states they can be difficult to learn when you're not a programmer. "Well, that's the impression I got when I saw them," he adds with a smile. "I looked at the websites, and I thought 'Yeah, I don't know if this is a whole lot easier than just writing the code," and he laughs. "I think it's an inherent problem in complex tools, that trying to document it or teach it is a real challenge, because you need that nested, layered approach. Where you have the most important information first, or to get something just functioning on it at a very rudimentary level, and then introduce more and more advanced layers to a person. It's true in software design as well. You can look at an interface and just be utterly overwhelmed, or you can see an interface and it's pretty simple. But then as you dive down it's well designed. There's more and more layers of power as you dig in, but you reveal them as needed rather than have it all there cluttering up the screen and confusing you initially."

But to get back to the proud moments, we asked Kevin what project he's most proud of in his movie career? "You know, I've done forums and different things and interviews, and that's a question people ask a lot," answers Mack. "And I always have a hard time with it. The other one is like 'what was the most challenging thing', I get that a lot too. I have the hardest time with it, because every job is different, and I've had so many great times on each of them, and miserable times on each of them. It's a tough one. If I had to pick one, I would say Fight Club just because I got to work on it kind of by myself for a long time, and then the team I had was small and really good and they were my friends. And David Fincher just kind of let me do it. He had a vision that he made really clear right at the get-go, and then just let me go. I got his vision, and he liked it. It was a pretty pleasant experience in general. So that was a great one, but I've had a really good time on others as well. I had a blast on Ghost Rider. Ghost Rider was a really fun project. A great team, and the crew, and Nick Cage... We were in Melbourne, Australia. I just had the best time. I thought the stuff looked really cool - I really liked how it turned out. I was really proud of the fire in Ghost Rider. Because at that time, noone had really solved it yet. People had done CG fire, but it didn't look authentic. I felt that we really solved it in that one, in a robust way that was able to play through a whole movie as a main character. The movie did well and I suppose it's not for everybody. A lot of the comics guys really liked it. But I'll tell you what; unlike everybody else, I pick apart most movies, and find most of them to not be any good. But I've been involved with enough of them and seen them being made by people who are pretty darn smart, and working together pretty well, and when you see the complexity of all of the roles and how they have to work together and relate to eachother, and how much is left to chance in the making of a movie... you realize that in the very best of situations it's a really, really hard thing to make a great movie. It's really, really, really hard. I think we all tend to kind of criticize them and we go 'Oh man, that's gotta be the biggest bunch of idiots I've ever seen. I could've farted a better movie than that.' [laughter] But then you kind of start to watch and pay attention, and it's really hard."

This makes it all the harder to be judged so harshly by some critics. "Oh yeah, it's tough," agrees Mack. "Those directors have got to be just made of steel. And even so, I think it just kills them to have their things torn apart. You know, they're trying pretty hard. They're not all perfect. Some guys are certainly brighter and better than other guys, but even so it's pretty brutal sometimes to see how these guys get shredded. In fact it's often not their fault. You know, with all the studio people making changes, and pulling money out from under them, and then recutting the movie and then giving them a week to fix what the person that recut it did, and you know - just one thing after the other. It's a constantly shifting game, that almost impossible to win. Even when you're at the top of your game, there's just so many elements of it that have very little to do with the creative process. Well, anyway, I'd just like to throw that out there in defense of the folks, because I see them and see that process and how it really works. I think people forget, you know. Even when you're in it, that's really the thing that's amazing, is you can be ON a movie, involved in that process, and not really be able to see where it went wrong. That's what makes it so hard. I look at movies all the time, and go 'Ah my god, what a piece of junk, how did that ever get made'. And I know how movies get made. I see the process. And yet, I cannot fathom how a movie can get made that is so bad, or equally so good. You see movies that are SO good, and you go, 'How did they DO that? How was that possible?' Against all the odds, and against all the problems of the process, and all the people involved. Such sublety and brilliance ... it's almost like there's this threshold. If a movie is good enough, it becomes almost divine.

Similar things can happen with demos too. Sometimes, something is released and there's such a big stir. For example, when Debris was released by Farbrausch at Breakpoint, the whole party just went like 'wow - what has just happened?' When talking to the Farbrausch guys, saying 'guys, that was amazing' they replied, 'Yeah, we didn't even expect it to be received that well. You see, if you've been watching it and making it for so long, you don't 'see' it anymore'. Farbrausch spent two years on it. It was very cool to you see Fiver, the guy who directed the demo, say that he was floating on air when he saw the reaction of the crowd. 800 people cheering and applauding. He said: "This is what I did it for. Seeing that reaction makes it absolutely worth it." "There's nothing like it," confirms Mack. "It's the coolest thing."

"I remember when I saw Masagin for the first time," continues Mack. "At the end of that one there's this kind of .... pattern, radial lines... kinda thing. With things floating in the middle. Then there's some colors in there, where lines are duplicated and red and green and slightly out of registration or something. Anyway, I have no idea how it was done. For whatever reason, when I get to that part of that particular demo, it's like something happens. I mean, it's psychoactive. I'm gone. I'm just somewhere else. I can feel it, like I'm inside it. It's like the whole universe collapses and expands, and I merge with the infinite. It's just, you know, it's unbelievable. It's a cool thing. And I wondered about not only how did they do it, but like what were they thinking. Was that inspired by a particular thing? Because I do yoga and meditate and do all kinds of things to alter my consciousness, and have experiences. Sometimes in some of the yoga things, and some of the breathing techniques, you get these visions. You get these things where you see stars, you know. Or when you stand up too fast, or whatever. You get the kind of checkerboard patterns and all kinds of things in your field of vision. That reminded me so much of that experience. I wondered if it was inspired by that at all."

"What do you guys think of all the tools that are coming along?" asks Mack. "There's all these real-time game engines, and they've got all the graphics cards, and you know - Intel and Nvidia and AMD are all coming out with stuff, and everything is going to GPU's. There's posturing and trying to move in on the real-time thing. There's people that are making tools not just as game engines, but for doing kind of the Second Life type of things, but with higher fidelity. Also, virtual 3d art galleries, and... there's a lot of stuff going on in that area now. I'm just kinda digging in to all of that, and seeing what is out there. I'm finding some pretty interesting things."

With the hardware getting better and better, and more stuff being done, there are so many more possibilities for the things you can do. It's very interesting to see, because the 4k intro category, that started like a decade ago, and with only graphics and no music, and has evolved into 4 kilobytes with real softsynths and... well, it's done in hardware, but it's still very impressive. The new intel cards that are coming out, that are going to have little cpu's, the Larrabee. It will be interesting to see what you can do with that. "Yeah, I'm very interested to see what can be done with that as well," confirms Mack. "One of the things that I noticed at Siggraph that seemed to be lacking a little bit, it's gotta be time for it to explode again, is Virtual Reality. In the early nineties, and even the late eighties, there was all this promise of virtual reality. We were gonna be wearing head-mounted displays, and we'd be shopping online, and we'd be standing in our livingrooms going on safari, ... and it just vanished. It just dried up. The graphics capabilites weren't quite there yet, it was really low fidelity, and then the headmounted displays were kinda tunnel vision - but the biggest problem was the lag in the headtracking. Now, all those things are solved. There are quite a few of those headsets on the market now, for 200 or 300 bucks. But they're really no good. They're not good enough. So I think the gamers just sort of gave up on them. The fact is, there is a handful of people that have kept at it, and developed the technology. The military is using it, and aerospace, and maybe a few other industries, but they make them one at a time since they only sell five a year at the most. So they cost a fortune. There is a company selling headsets that have a 150 degree field of view, and are 4000 pixels across. So they're really high res, and there was no latency at all. I tried that thing on at Siggraph, and it just blew me away. I was there, in this virtual world, and I reached out for a chair that was sitting beside me in the virtual world, and I was completely freaked out by the fact that my arm just wasn't there. Of course, they have the standard gag where you look around and you look down next to you, and there's a huge hole in the ground. Just drops into an abyss. So I lean out over this big hole carved in the ground, and meanwhile, I'm just standing in a booth. But I'm looking down into this hole in the ground, and I had total vertigo. I felt like I was just going to get sucked into it, it was so real. My dream is to do this kind of abstract, realtime, crazy-ass worlds stuff, but do it interactively so that people can explore it. People can navigate through it. Maybe they can affect it a little bit or something. It's more just about them being immersed in it. Even if you can't do anything but look around, and see this demo going on around you, this crazy psychedelic thing, in full 3d stereo. How cool would that be? Would that blow some minds or what? I also tried the 3d glasses, and while they had the latency problem, and weren't very good resolution, you know they worked a little bit. They weren't THAT bad. They were at least promising. I don't understand, it's been 20 years, and nothing. We've got nothing now. I want my Virtual Reality, and I want it now."

"I want my virtual reality, and I want it now."

True, it was promised to us! "Yeah, exactly. And you could adapt anything! You could adapt anything in 3d to it easily. Those goggles, the headset thing, they got to get the price of that down. I tried this one that was just so amazing, but they were making them one at a time and they were $54,000 dollars. That kinda puts it a little out of my range, and most gamers', probably. I think that they said that they had their fingers crossed and that they were talking to some big game companies. Once they can start making them 20,000 at a time, the price is gonna drop way, way down. Because it's not that different, fundamentally, from the ones they're selling for 300 bucks. They're way better, but they're not really technically that different."

So, after having touched loads of planned and unplanned topics, it became clear that Kevin Mack is very interested in the scene and in all sorts of other things that have to do with computer graphics and art. It was a truly inspiring conversation and ZINE would like to shout out a big 'thank you' to Kevin for having dedicated his time to do this interview.

We look forward to the adventures that are yet to come, and the realms that will still be explored.

Comments